Retiree Helps Fellow Nuclear Workers Apply for Cancer Assistance in Oregon

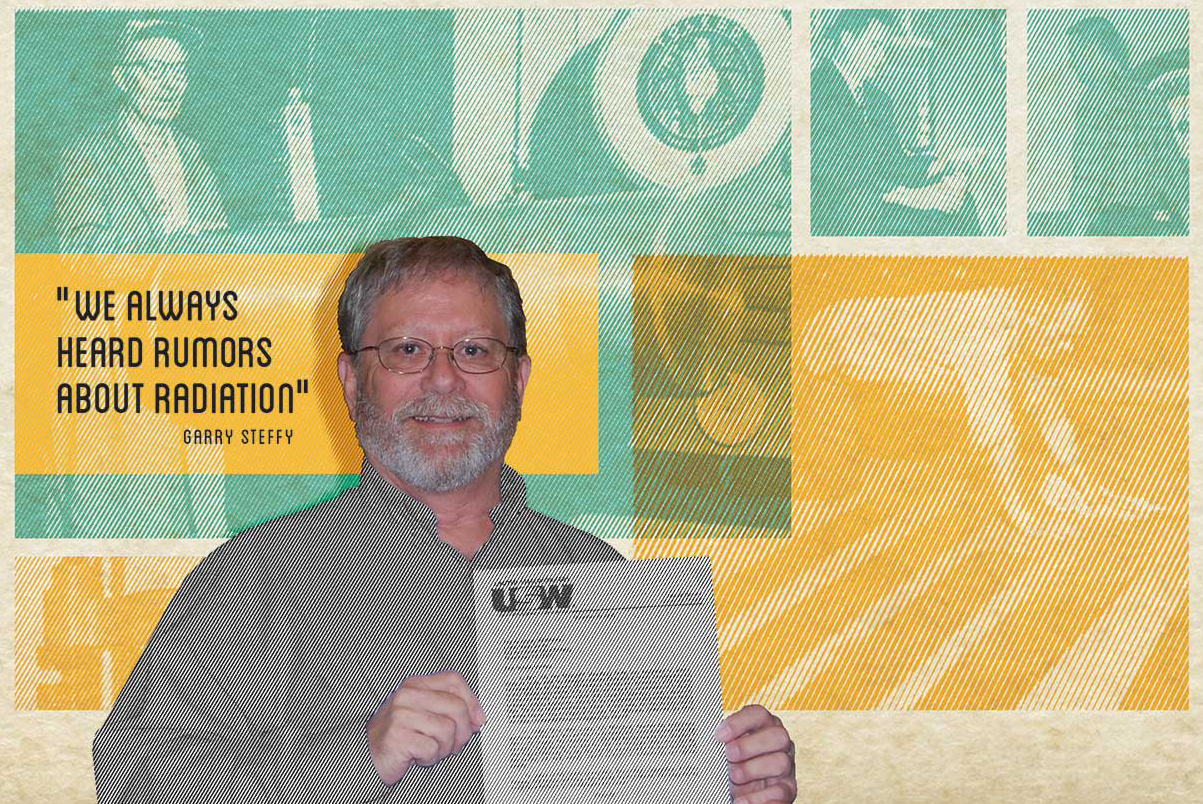

Garry Steffy typically starts his day with a cup of coffee and a quick look through the newspaper for obituaries of people who once worked for ATI Specialty Alloys and Components in the small town of Millersburg near Albany, Ore.

This daily routine is more than a retiree’s curiosity. Steffy has made a mission of searching for USW members and former co-workers who qualify for a special government compensation program for those exposed to radiation while working on the U.S. nuclear weapons program.

“We have a rare opportunity here to assist our brothers and sisters,” Steffy, a District 12 coordinator for the Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees (SOAR), said during an interview also attended by Albany Chapter 12-7 Trustee Eugene Jack. “Me and Jack, we’re old Steelworkers. We’ll go to the end to help.”

Over several years, Steffy and his fellow SOAR members led the charge in spreading the word about the compensation program. They have helped hundreds of ATI retirees, employees and their families receive more than $42 million in federal compensation and medical benefits. And that number will most likely continue to grow.

“I love when people get the money,” said Steffy, who started Oregon’s first SOAR chapter after he retired from ATI in 2010 with 36 years of service. “But I hate that they had to suffer to get it.”

Congress passed the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Act (EEOICPA) in 2000 to provide benefits to nuclear weapons project employees who were sickened by exposure to radiation and/or other toxic substances. Survivors of deceased workers were also eligible to file claims.

The metals refinery in Millersburg can trace its ownership to a company that began operations in the 1900s as the Wah Chang Trading Co. In 1956, the Atomic Energy Commission, now the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), contracted with Wah Chang to develop and produce a high-purity zirconium for the U.S. Navy. Zirconium is used to contain radioactive uranium used in nuclear reactors and on the Navy’s nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers.

The facility, now owned by Pittsburgh-based ATI, a global manufacturer of technically advanced specialty materials, remains a major refiner of zirconium as well as other exotic metals such as hafnium, niobium, tantalum, and vanadium. It is one of the largest producers of rare earth metals and alloys in the United States.

Melting uranium

In the 1970s, Wah Chang was contracted by Union Carbide Corp. to melt uranium-bearing material from the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tenn. Union Carbide operated Y-12 from 1947 to 1984 for the Atomic Energy Commission and the DOE.

A special furnace called S-6 was used to melt the material, which was pressed into billets or ingots and shipped back to Oak Ridge. It later became clear that not all of the radioactive material was removed.

The facility in Millersburg, which claimed a population of 1,329 in the 2010 census, was designated an atomic weapons facility in 2011 under the EEOICA and awarded special cohort status. Under that status, workers who contracted one of 22 listed cancers were eligible to file a claim and receive compensation of $150,000 and medical benefits for life.

If you did not qualify in that part of the program, employees could be compensated under a more complicated “dose reconstruction” formula that considers age, gender and areas worked. Claims would be approved if the numbers added up to a 50 percent probability that an employee may have contracted a cancer from radiation while employed there.

Steffy learned in 2011 from a newspaper notice that he and co-workers at ATI Specialty Alloys, widely known to locals by its previous name Wah Chang, had been exposed to radioactive materials.

Unbeknownst to Steffy, the family of former Wah Chang employee Roy Backer in 2010 petitioned the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to declare workers at the plant eligible for benefits under EEOICPA.

Most workers at the Millersburg plant were never told about the uranium that was processed there or warned to take extra precautions, according to Steffy and a series of reports in the Corvallis Gazette-Times by Bennett Hall.

“We always heard rumors about radiation,” said Steffy, who for 25 years operated the S-6 electron beam melting furnace that processed the uranium from Y-12.

Notification letters

After Steffy heard about the program, he started to campaign to let ATI employees know. In the early stages, the company would not publicize the compensation program, but would confirm employment when requested by the program administrators.

Steffy also contacted local attorneys and funeral homes all around Oregon to look for ATI retirees who may have contracted cancer. SOAR several times sent hundreds of notification letters to retirees.

“I’ve gone to nursing homes to visit people who were literally on their last dime in their checking and savings accounts and they get this check,” he said. “It takes the pressure off them and their family.”

In March 2016, as ATI was ending a six-month lockout of 2,200 USW members nationwide, the Millersburg facility stopped responding to requests by the Department of Labor for employment records of former employees seeking the radiation compensation.

In refusing to verify employment, the company caused claims for compensation to be denied. That prompted Steffy to contact U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio and U.S. Senators Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden, all of Oregon.

After political pressure from the Oregon delegation, ATI Millersburg resumed employment verification in October 2016, and, for the first time, sent out letters to all current and retired employees informing them of the federal compensation program.

“In most cases, this was the only proof of a worker actually being employed at the plant,” Steffy said. “If these men had not stepped up to the plate and helped out, frankly I do not know where we would be now.”

The three politicians were publicly thanked for their intervention in late 2018 in a letter signed by International President Leo W. Gerard and District 12 Director Robert LaVenture.

“Garry should be given credit for his hard work and desire to bring justice to this issue,” LaVenture said. “Garry, like many of our SOAR members, never quit wanting to help others after he retired.”

Task not over

Steffy credits SOAR, the late International President Lynn Williams, who created the retiree program, and his local union President Jim Kilborn, for asking him to get involved with the organization.

The ordeal is not yet over. Steffy is asking the government to expand the program to include additional areas of the refinery, a request that could help others who worked around the S-6 furnace. Some areas, he said, were never decontaminated.

“We had a ventilation system that would suck the dust out, and in the winter it would blow hot air on you. They never cleaned that out and through the years people would breathe in this radioactive dust,” he said.

Steffy is seeking records from NIOSH and the Center for Disease Control that he believes might make the case. But unable to pay an estimated $5,000 records fee, he has sought help from Sen. Merkley to get the documents.

If he prevails, Steffy thinks another group of employees and retirees may receive enough additional credits or points to qualify for an additional $25 million in assistance.

In the meantime, Steffy continues looking out for other retirees and, occasionally, himself. He undergoes a physical twice a year with the knowledge that he could be diagnosed with cancer.

“I know I’ll get it because I worked around the stuff,” he said. “I’m just waiting until the doctor tells me I have it.”

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Recent News Articles

Want to Learn More?

See how the USW is making a real difference in our communities and our workplaces.