USW Members Protect & Serve

Kyle Achtyl never knows quite what to expect each day when he arrives to work as a deputy sheriff in Niagara County, N.Y. And that’s the way he likes it.

“No two days are the same,” Achtyl explained recently as he prepared to head out for his afternoon shift in the picturesque region of about 210,000 residents along Lake Ontario in northwest New York.

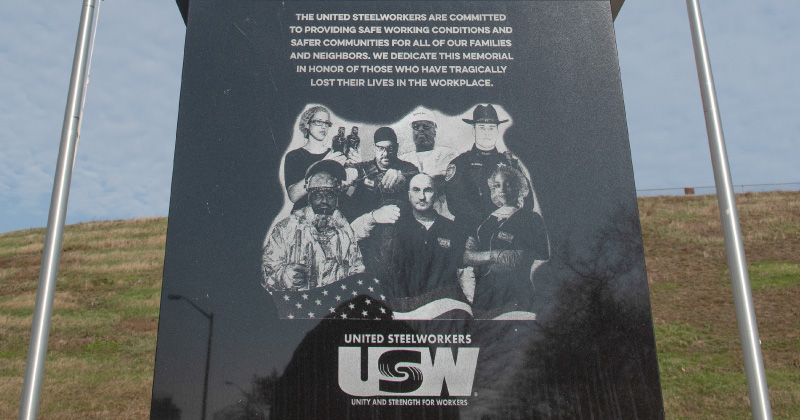

Niagara County is home to about 105 members of Local 4-2001 who serve as deputies, investigators and other law enforcement agents for the county sheriff’s office. They are part of a larger group of more than 600 USW members who serve in a similar capacity across the United States, and more than 25,000 public workers in the USW overall.

The unique nature of their jobs makes the work days exciting but also unpredictable and potentially dangerous for Achtyl and his fellow Local 4-2001 members.

Facing Difficult Days

Local President Brian Bloom, an investigator, has been with the sheriff’s office for 10 years after putting in five years of service with the New York State Park Police. He said that while he has had plenty of traumatic days on the job, he tries to begin each new shift with a clean slate.

“Everybody deals with it differently. I try not to take it home with me,” Bloom said of job-related stress. “I’m not sure I could even tell you what my worst day was.”

As with any other USW local, the members in Niagara County are focused on the well-being and safety of their co-workers, although for law enforcement officers, ensuring a safe workplace looks a bit different than it might in an industrial setting.

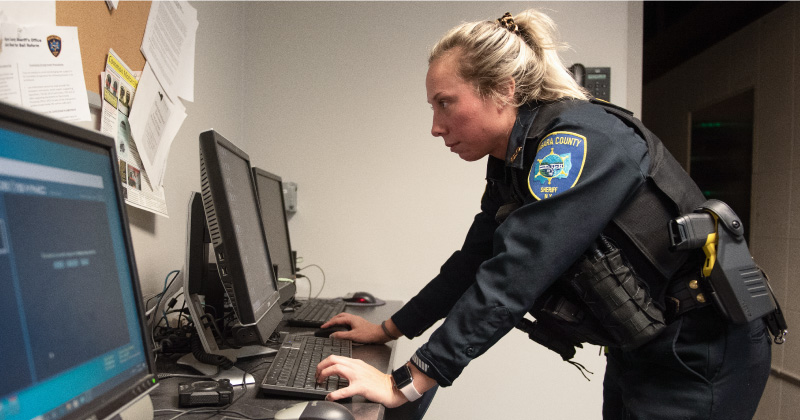

Wearing vests loaded with equipment from communications devices to weapons to first-aid tools, the officers acknowledge that some bystanders may view the resulting appearance as intimidating.

Deputy Sheriff Joseph Flagler noted that officers’ equipment is more visible than it once was – they now wear much of their gear on their vests rather than their belts to avoid back problems. A better understanding of why and how officers carry the equipment they do could help to alleviate issues of trust, he said.

Bloom acknowledged that fact but said the officers’ job is – as the maxim goes – to protect and serve their community, while making sure every member comes back safely at the end of their shift.

“This equipment protects us, but it’s not for us to go on the attack,” Bloom said. “At the end of the day, it’s about us getting home alive.”

Part of Labor Movement

The Niagara County officers have long been part of the labor movement in heavily unionized Western New York. They were members of the Paper, Allied Industrial, Chemical and Energy Workers (PACE) until 2005, when that union became part of the USW.

The USW local in Niagara negotiates their collective bargaining agreements across the table from a committee led by the county manager.

Bloom said that having a contract in place to support the Niagara County work force helps to ensure that members are treated fairly regardless of who sits on management’s side.

“You have a voice,” he said. “It doesn’t mean you won’t have problems, but it means you can sit down and talk about them.”

Wide Range of Duties

While Bloom and the other members of the local regularly deal with day-to-day issues such as criminal investigations and traffic violations, their work extends far beyond those duties into more complex situations such as hostage negotiations and drug trafficking.

The sheriff’s office includes an aviation unit equipped with a helicopter, a marine patrol unit, a SCUBA-certified underwater response team, a canine unit, a search-and-rescue unit, and an emergency response team that answers calls to the most volatile situations.

Because Niagara County is easily accessible by road, water and air from neighboring Canada, USW members also work in conjunction with state and federal agencies, including the U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Coast Guard, and are part of a task force charged with stopping the flow of illegal narcotics and other dangerous substances.

Focusing on Safety

Bloom said he knows that some in his community may view law enforcement officers with mistrust or skepticism, given the high-profile deaths last year of George Floyd in Minnesota, Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, among others, and the resulting nationwide demonstrations. Still, he said, the officers he has worked with in Niagara County and elsewhere are committed to making sure every member of their community is free from harm.

“Our goal is to be safe and for others to be safe,” Bloom said. “We never show up with the idea of doing harm. Using force is the last thing anyone here wants to do.”

Flagler said he works hard to put other members of the community at ease when he is on the job patrolling Niagara County’s neighborhoods.

“You’re in your uniform, and you don’t even think about it,” Flagler, a 30-year veteran officer, said of his on-duty appearance. “It’s like a second skin.”

One piece of equipment all deputies in Niagara County employ is a body-worn camera, which records each interaction that an officer has with the public during their work day. USW members say the cameras are there to ensure safety – both of the public and the officers who are called to serve them.

“Who else goes to work every day with an eye on everything they do?” Flagler asked. Such cameras have helped to protect the public, and hold officers accountable, while also often vindicating officers who have been accused of wrongdoing. He noted that making the use of the cameras is “one of the best things that has happened.”

Task Force Aims at Reform

As the national conversation last year turned to issues of systemic racism and police brutality, International Vice President Fred Redmond tapped Bloom to serve on an AFL-CIO subcommittee within the recently formed Task Force on Racial Justice charged with recommending changes to community policing and public safety. The USW is one of 13 AFL-CIO unions that count police officers as members.

“It’s a slow process, but we are making progress,” Bloom said of the task force, which has been meeting, virtually, every two weeks since last fall.

Bloom said that while calls for reform are rightly highlighting the need for more community investment in areas other than policing, he said he wants to make sure that the movement doesn’t turn into an attack on the rights of union workers.

As Bloom pointed out – from the perspective of a labor leader – reductions in funding could threaten the good jobs, pay and benefits that the USW membership provides to working families like his.

“Just ‘defunding’ is not the answer, but we don’t have a problem having the conversation. Let’s get people together and let’s have conversations,” Bloom said, noting that more funding – not less – is the answer across the board, so that municipalities can invest in more intensive training for officers, as well as in other community-based programs to help ensure the public welfare. “We need to work with the government and get money devoted to different things.”

Redmond said that too many government officials in the United States are trying to use the current climate as an excuse to attack collective bargaining, which is the wrong approach.

“What we are trying to do is create a new blueprint on public safety,” Redmond said. “Some of these municipalities, they’re coming after collective bargaining under the guise of reform, and that’s all wrong. Communities would benefit from a more holistic approach that includes the labor movement.”

Redmond said that unions must be part of the discussion as the nation grapples with ways to reform and improve community relationships with public safety professionals.

“We are taking a quite different approach – we are saying that collective bargaining can be the solution to a lot of our issues,” he said.

‘On Board with Reforms’

Redmond and Bloom both said it’s important to remember that the vast majority of police officers, in Niagara County and across the country, are workers with families and children who care about their co-workers and the people who live in their communities.

“We have to see some of these reforms through the eyes of the people who do this work every day,” Redmond said. “The overwhelming majority of good people in this profession support positive reforms. They want the bad apples held accountable and removed.”

The USW supports the adoption of a set of national, professional standards for unionized public safety officials, Redmond said.

New York state already has strict guidelines for police officers on the use of force, and the Niagara County officers have a detailed policy that puts them ahead of their counterparts in other areas of the United States, Bloom said.

“We’re on board with a lot of these reforms already,” he said.

Community Support

While upholding their duty to serve and protect their neighbors, the members of Local 4-2001 go even further to support their community, raising thousands of dollars each year through various fundraisers, which they in turn donate to causes throughout the region, including local food banks, child advocacy groups, domestic violence-prevention programs, children’s athletic teams and summer camps, holiday toy drives and other charities.

Flagler said that through October 2020, the officers’ charitable fund had already exceeded the total amount it collected throughout 2019. He took that as a signal from residents that they have the officers’ backs.

“Our community here supports us very well,” Flagler said. “And we appreciate it.”

Besides gaining the respect of the people of Niagara County, officers have received national attention for their work. In 2016, President Obama awarded the Presidential Medal of Valor to Niagara County Deputy Joe Tortorella, who confronted and subdued a gunman who had shot his parents, preventing the gunman from harming students at a nearby school.

Bloom said that the positive relationship the USW local maintains with management has helped the entire region of Niagara County.

Sheriff’s deputies help to patrol 12 distinct zones in the county they serve, some of which have their own police departments and some of which rely on the county sheriff’s office and the state police as their primary law enforcement agencies.

For each shift, the county has a minimum of six officers in patrol cars at all times. The office fields an average of more than 200 calls per day.

Most of the members of management in the office, including Niagara County Sheriff Michael Filicetti, worked their way up through the rank and file. That has helped to make the relationship between management and Local 4-2001 more productive, Bloom said. Management knows what kind of equipment and support officers need to get their jobs done right and to remain safe, and they make sure the members have it, he said.

That mutual respect extends to the public, which must vote to elect the sheriff in Niagara County. That gives local residents a stake in what happens in the sheriff’s office, Flagler said.

“The public respects that,” he said. “They know exactly what we do every day.”

Flagler said that the union and the sheriff’s office also share a commitment to strict training and certification standards, which has helped the office to build a positive reputation within the community.

The members of Local 4-2001 undergo a rigorous training regimen, both when they are new to the profession and continuously throughout their careers. New recruits must complete at least 24 weeks of police academy study, including four weeks of on-the-job training, as well as two to three more months in the field. They also undergo continual firearms training as well as regular anti-bias and anti-harassment programs.

Before joining the sheriff’s office, deputies must pass extensive background and physical fitness checks, Bloom said.

“We are constantly training,” he said.

In addition to regularly taking classes, USW members also teach them. They are among the instructors at the Niagara County Law Enforcement Academy on the campus of Niagara University, just a few miles from the office headquarters.

The academy provides training for officers in Niagara County as well as several nearby communities on subjects including civilian dispatch training, impaired driving detection, accident investigation, police supervision, homeland security and other topics.

Keeping their skills fresh and staying up to date on law enforcement standards helps officers maintain community trust, Flagler said.

Bloom said that even though he sometimes worries that “mistrust breeds mistrust,” he hasn’t let the changing landscape of law enforcement in the United States alter his basic approach to his job. He still approaches every call the same way.

“We are all human beings,” Bloom said. “Every life is valuable, and we need to treat it like that.”

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Recent News Articles

Want to Learn More?

See how the USW is making a real difference in our communities and our workplaces.