Bargaining for Stop Work Authority to Prevent Injuries and Save Lives

Published July 1, 2022

Stop Work Authority (SWA) is the right of workers to stop unsafe work and processes until the potential hazard is thoroughly investigated and abated to the satisfaction of workers, the union and management. This publication is intended to help local unions win effective SWA processes in collective bargaining agreements with management.

- Part 1 explains how the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) and other laws do not include SWA; how SWA programs are actually common in workplaces; that a voluntary consensus standard supports SWA, as do many safety professionals; how workers face challenges when using SWA; and how workplace health and safety issues, including SWA, are a mandatory subject of bargaining under the National Labor Relations Act.

- Part 2 provides a model negotiated SWA process and contract language won by a USW local union.

- Part 3 provides four checklists to help develop an effective SWA process.

- At the end of this publication, the appendices, resources and endnotes provide more information, including a USW template of model language for the Right to Act and Stop Work Authority Process – Appendix I.

A strong, participatory role for workers and local unions is essential for workplace safety and health. This includes the right of workers to pause or halt a task – or even stop a major operation or process – that they reasonably believe is unsafe or unhealthy. The right to stop unsafe work processes should continue until the hazard is thoroughly investigated and abated to the satisfaction of workers, the union and management. Workers must be able to exercise this right without fear of retaliation or discipline.

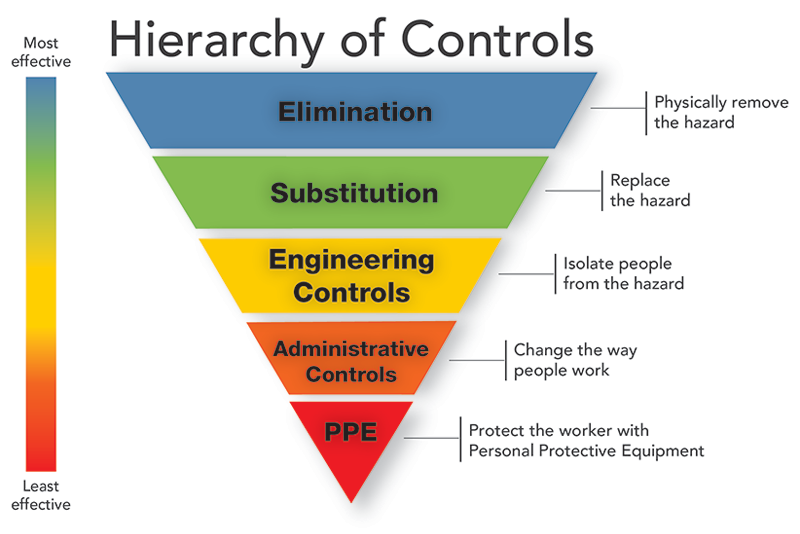

This right is called Stop Work Authority (SWA). SWA can save one’s own life and the lives of fellow workers. SWA, however, should never be the primary way to address hazards. Instead, the Hierarchy of Controls, illustrated below, should be applied to prevent or control hazards.

Stop work authority is an important administrative control and worker right that plays a key role among other, more effective strategies to prevent or control workplace hazards.

The hierarchy of controls approach shows us that SWA policies are not the USW’s top strategic choice to prevent hazards, but they are an important and potentially life-saving backstop if other steps fail.

SWA can be challenging to implement successfully. Once established, this process may require workers and union representatives to debate with – and sometimes come into conflict with – their supervisors, management and even co-workers. Management may try to retaliate against those who exercise this right. But, when other safety and health protections fail, a strong negotiated SWA policy offers workers and their representatives an essential right that may be critical to preventing injuries and saving health and lives. It gives workers and their representatives protection to do the correct and safe thing even when the pressure of getting the job done is pushing them to proceed with dangerous work that should not be done. When a worker is facing a poorly shored trench or a questionable confined space, handling poorly maintained equipment, given inadequate personal protective equipment, or working on a unit that might explode, a good SWA process allows workers to halt or stop the job or task, or even a major process or operation.

SWA is most effectively exercised by groups of workers engaged through their union rather than by individuals acting alone. Employer retaliation is much less likely when workers act together through their union.

SWA does not substitute for an employer’s legal duty under the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) to ensure a safe and healthy workplace. Employers must NOT use SWA policies to shift responsibility and blame workers for not stopping work. An effective SWA process in a collective bargaining agreement and in the employer’s written procedures should include a prohibition on blaming workers for failing to use this process.

SWA should be part of every employer’s written health and safety program and union collective bargaining agreement. Unions should bargain for strong SWA contract language and do this before members need to use it. Local unions should contact their USW’s district staff representative and the USW’s Health, Safety and Environment Department for assistance with SWA issues.

This publication explains what should be covered in an effective SWA process and collective bargaining agreements, offering guidance for health, safety, and environment committee members, local union leaders, and USW staff.

Part 1A: The Occupational Safety and Health Act and the National Labor Relations Act

Neither the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) nor the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) offer as much protection as a strong SWA process won through collective bargaining.

Section 11(c) of the OSH Act prohibits discrimination against workers who exercise their legal rights to a safe workplace. Under this authority, OSHA has adopted regulations that provide workers the right to refuse imminently dangerous work, without fear of reprisal, until the condition can be investigated by OSHA using their standard enforcement mechanisms and, when necessary, resolved by the employer.

The NLRA also provides a limited legal right to employees to refuse unsafe work.

Yet neither the legal rights under OSHA nor those under the NLRA offer as strong of protections as SWA, which should be a collectively bargained policy that gives workers and their representatives the clear, contractual right to pause or halt a task, operation, or process until hazards are investigated and addressed. The SWA policy should include not only a right, but also a clearly communicated procedure for workers and their representatives to exercise their SWA.

While the OSH Act does not include SWA, some OSHA standards require employers to have a very limited form of SWA. These include standards for industries that use highly hazardous chemicals and for cranes and derricks in construction.

OSHA’s standard for Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals (PSM) covers many chemical plants, oil refineries, paper mills, and other facilities that involve using more than the specified quantities of highly hazardous chemicals. The federal PSM standard states that these employers must have procedures for Emergency shutdown, including the conditions under which emergency shutdown is required, and the assignment of shutdown responsibility to qualified operators to ensure that emergency shutdown is executed in a safe and timely manner.

OSHA’s standard for cranes and derricks in construction states;Whenever there is a concern as to safety, the operator must have the authority to stop and refuse to handle loads until a qualified person has determined that safety has been assured.”

OSHA’s PSM and crane standards, however, are not designed to empower workers acting through their union across the industry.

California OSHA implemented a new PSM standard for oil refineries in 2017 that authorizes all employees, including employees of contractors, to recommend to the operator in charge of a process unit that an operation or process be partially or completely shut-down, based on a process safety hazard. It also authorizes the qualified operator in charge of a process unit to partially or completely shut-down the operation or process, based on a process safety hazard, without having to obtain authorization from the refinery management (see Appendix II). But this standard applies only to California oil refineries.

Local unions should not wait for federal OSHA or state OSHA agencies to issue standards requiring SWA. They can achieve or improve SWA policies and procedures through collective bargaining.

Part 1B: Employer Policies

The USW has won strong SWA processes in a number of local bargaining agreements. For example, an agreement at Chevron Phillips Chemical Company reads: “Work that has ceased due to Stop Work Authority/Shutdown shall not be resumed until all personnel safety aspects have been discussed with affected personnel and consensus to resume has been achieved.” The USW also successfully developed strong SWA processes, such as at Delaware City Refining in Delaware City, Delaware, as discussed in Part 2.

While there are few studies of SWA programs in the United States, it is clear that various employers already have these policies. BP reports that they “…empower anyone to stop a job if something doesn’t seem right.” The Southern Company’s SWA policy “…empowers employees and contractors to stop individual tasks or group operations when the control of health, safety, and environmental (HSE) risk is not clearly established or understood.” According to the American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry’s largest trade association, “API members support and have implemented ‘stop work authority programs’ and consider such policies a matter of their corporate safety cultures.” API even maintains – without offering evidence – that “All workers [in the oil industry] have stop work authority.”

Because there is no law mandating SWA, the SWA process is specific to an employer or workplace. The employer having a policy must not be a substitute for a negotiated SWA. The union negotiated SWA should be part of management’s safety and health written program. All levels of management, including first-line supervisors and top executives, should understand and support SWA and work with the union(s) to implement it. Having SWA in their collective bargaining agreements will allow unions to address situations where this support is lacking.

Part 1C: Industry Voluntary Standard Supports SWA

The American National Standards Institute/American Society of Safety Professionals Standard Z10-2019, Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems, is a national voluntary safety standard that may help management understand and adopt SWA. It includes a provision calling for company policies that ensure awareness among workers to:

The USW and other unions helped develop and approve this voluntary standard, along with corporations and trade associations, including Alcoa, Chevron, Nucor, Siemens, United Technologies, the American Chemistry Council, and the American Foundry Society.

This voluntary standard’s language is limited and is not a substitute for negotiating a comprehensive SWA policy. It may be useful, however, to cite employer support for this standard when pushing for and negotiating SWA at your workplace.

Part 1D: Industry Safety Professionals Support SWA

The Center for Chemical Process Safety of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (CCPS) is funded by chemical and oil companies, and many of these companies have contract agreements with the USW. CCPS books on process safety state that:

The CCPS also states:

Part 1E: It Can Be Difficult to Stop a Hazardous Job, Task, or Operation

SWA decisions are typically made during upset conditions or emergencies in unforeseen, unknown, chaotic, and highly stressful circumstances when there is little or no time available for careful thought and decision-making. In some situations, such as when the process is already shut down by an incident, it’s too late to invoke SWA unless management wants to restart the process before problems have been corrected.

Also, the reality in many workplaces is that workers are extremely reluctant to pause or stop a job. This is especially true if it involves a major unit in an oil refinery, chemical plant, paper mill, or other type of operation with interconnected processes. The shutdown of such processes can sometimes be expensive, or perceived to be so, even if the incident it prevents could potentially cost far more in money, health and lives.

When workers are reluctant to use SWA, it is often for understandable reasons. These can include:

- Fear of management retaliation, including discharge.

- The assumption that hazards are part of performing the work.

- Feeling that it won’t make a difference since management has not corrected previously reported hazards.

- Production pressures.

- Work organization factors, such as understaffing, unclear or conflicting roles and responsibilities, etc.

- Concern about delaying job completion and costing money.

- Belief that the decision should be made by management, not hourly employees.

- Lack of a written procedure that explains criteria for when specific machines, equipment, units, etc., should be shut down.

- No training to explain when and how to use SWA.

- Pressure or lack of support from co-workers and/or first line supervisors.

These challenges for workers who face decisions about stopping dangerous work are all the more reason for unions to negotiate safety and health programs with effective, clearly communicated SWA processes.

Part 1F: Health and Safety is a Mandatory Subject of Collective Bargaining

Under the National Labor Relations Act, health and safety is a mandatory subject of collective bargaining in private sector workplaces. Thus, at a unionized worksite, if either management or labor requests it in a collective bargaining process, the other side must bargain in good faith over safety and health issues, including SWA.

Local unions should consider negotiating with management a “Right to Act and Stop Work Authority Process.” As stated before, this is important because it takes the SWA from a policy that a worker may or may not know about or believe they have the authority to undertake, to an actual process that the worker, or group of workers and their union is empowered to start.

In 2021, USW representatives from Local 4-898 of District 4, their staff representative, the USW’s Health, Safety, and Environment Department, and management from Delaware City Refining Company worked together to improve their “Right to Act and Stop Work Authority Process.” Below is their Memorandum of Agreement from their collective efforts, as well as the text of SWA wallet cards distributed to the workforce:

The Right to Act and Stop Work Authority Process

- All employees will continue to be informed of the Right to Act process and instructed on how important it is to prevent fatalities, injuries, illnesses, and adverse events, and how critical it is to maintain and respect the process going forward. The Right to Act and Stop Work Authority is stopping a job/task/process that is believed to be unsafe/unhealthy and is also about identifying, preventing and controlling the hazards – short and long term. If you see something that is unsafe and/or unhealthy, we want you to say and do something without fear of consequences.

- To accomplish this Right to Act and Stop Work Authority process, each employee, in good faith, is empowered to assess each work situation and if he or she believes it is unsafe/unhealthy, or in violation of a safety or health policy or known safety or health standard, stop the job or task or operation, then engage their supervisor and union steward by sharing the concern for their safety/health, and/or the safety/health of others, if the specific job or task or operation were to be performed. The employee(s) shall communicate to their supervisor that they are not willing to perform the required job or task or operation because of identified safety and/or health risks that could result in injury to themselves, other employees, the environment or result in damage to the physical facility.

- Upon notification of the concern to their supervisor and union steward, it is the responsibility of the supervisor to assess the situation with the employee(s), and if needed consult with additional layers of management and Local Union Health and Safety Committee Representative(s) to review the situation and confirm that the risks as identified do or do not exist.

- If the safety and/or health concern(s) are not resolved by this involvement, the process will continue by engaging the department manager and local union president to assess the situation and communicate their findings to the refinery manager. If upon concluding such an assessment, the situation is determined to be unsafe and/or unhealthy, the employee(s) and anyone else shall be directed by management to not perform the assignment until it is safe to do so. The VP of Health, Safety and Environment, and the USW’s Health, Safety and Environment department director (or designee) are available to assist in this process.

- Each of these specific situations must be entered into the “Impact System” (electronic reporting system). Such a situation will be periodically reviewed by the JHSC and impact review process for system improvements refinery-wide as a Right to Act and Stop Work Authority.

- All employees (union and management) shall be trained annually to be competent in carrying out this process. In addition, new employees, before they begin work, shall be trained to be competent in carrying out this process.

- Under no circumstances shall employees be discriminated or retaliated against for using this process. For the employee(s) who refuses work and all employees affected by the refusal, there shall be no loss of pay, seniority, or benefits during the period of refusal, even if it is later determined that the alleged unsafe or unhealthy condition did not exist.

- Wallet Card – “The Right to Act on Unsafe/Unhealthy Work” card the Company and the Union agree to co-sponsor is meant to proactively engage the workforce. A wallet card will be issued to all hourly and salary paid personnel. The highest-ranking company executive and local union president will sign the card. On one side of the card it will state, “Employee Right to Act on Unsafe/Unhealthy Work – Occupational Health and Safety Shall NEVER be Sacrificed for Profits or Production” and will include company and union logos as well as a pictogram of a “Stop” sign. On the opposite side it will state, “As an employee, you have the authority, without fear of reprimand or retaliation, to immediately STOP any work activity that presents a hazard to you, your co-workers, the environment; to get involved, question and rectify any situation that is identified as not being in compliance with our Safety and Health Values and Policies; to report any conditions or activities to management and question any work that may cause harm.

USW’s Standard Steel Industry SWA Language Includes Arbitration for Disputes

The USW has won SWA language in collective bargaining with the standard steel industry that includes provisions for arbitration when the union and the employer disagree on SWA as to how a safe/unsafe issue is to be addressed and bring an issue to conclusion.

Below is the language from the master basic labor agreement with Cleveland Cliffs:

Section C.

The Right to Refuse Unsafe Work

3. If after the investigation it is determined that the condition existed, the employee will be made whole for any lost time in connection with the condition. If after the investigation the company does not agree that an unsafe condition exists, the union has the right to present a grievance in writing to the appropriate company representative and thereafter the employee shall continue to be relieved from duty on the job. The grievance will be presented without delay directly to an arbitrator, who will determine whether the employee acted in good faith in leaving the job and whether the unsafe condition was in fact present.

4. No employee who in good faith exercises his/her rights under this section will be disciplined.

5. If an arbitrator determines that an unsafe condition within the meaning of this section exists, s/he shall order that the condition be corrected and that the correction occur before the employee returns to work on the job in question and the employee shall be made whole for any lost earnings.

Across the USW, there are many other collective bargaining agreements with SWA language which the union continues to make improvements on.

Before bargaining for health and safety, use the four checklists in this section to help review your employer’s health and safety efforts and to develop SWA contract language proposals.

Part 3A: Questions to Ask Before Designing the Process

SWA will be most effective if certain conditions are met first.

- Is there an effective process to thoroughly identify and correct all potential hazards in operations, processes, and tasks?

- Are safeguards implemented using the Hierarchy of Controls in proper sequence, beginning with serious consideration of the most effective strategies, even if they are the most expensive? See illustration on page 4.

- Is the employer unfairly putting workers at risk by relying on them, through SWA, to abate hazards caused by the employer’s poor safety and health program, including inadequate staffing and maintenance?

- Is there a process for the employer to report back to the workforce about how hazards were or will be corrected?

- Before anticipated workplace changes are made, is there a thorough management of change (MOC) process in which workers and union representatives can meaningfully participate when the process begins? (MOC must ensure that risks are evaluated and prevented before implementing changes).

- When “organizational changes” are anticipated that can impact safety and health, such as job combinations, decreasing staffing, or a corporate merger or acquisition, is there a thorough management of organizational change (MOOC) process to identify risk in which workers and union representatives can meaningfully participate when the process begins?

- Is there a process for everyone in the workforce, including contractor employees, to assess and report hazards to management, including unsafe and unhealthy conditions, near misses, work-related illnesses and injuries, and related concerns?

- Is it clear that blaming workers, retaliation, and discipline by management will not occur under any circumstances when it comes to actions taken by workers to protect their safety and health?

- Have the union and management ensured there are no policies, programs or practices which could discourage workers from reporting incidents, hazards, near-misses, or injuries and illnesses; for example, rewards for zero injuries?

- Does management share process safety information with workers and their union representatives, and are changes made regularly to ensure it is up-to-date?

- Does management, overall, support meaningful involvement by workers and their union representatives on health, safety, and environmental issues? For example, is the union(s) offered a seat at the decision-making table early in the process, or are union representatives simply asked to review final decisions?

- Do all parties participate in a meaningful way, including facility management, corporate safety and engineering departments, union representatives (including contractor employee union representatives) during all stages of hazard identification, prevention and controls?

- Is there an effective health and safety training (and refresher training) program?

- Is there an indicators program to compile facts and analyze trends about incidents, including near-misses, and to assess current health, safety and environmental systems?

Part 3B: Key Elements of an Effective Process

The written SWA process should include defined roles for individuals, including layers of management and safety and health committee(s). This process should also specify what general circumstances and specific situations could trigger the use of SWA rights.

Clearly Defined Roles

Are there clearly defined roles for the following individuals at the site and corporate levels?

Management

- Immediate Supervisor

- Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) staff at the facility (including engineering, process safety, industrial hygiene, etc.)

- Area or Process Managers

- Facility Manager

- Corporate EHS Director

- Corporate Executive(s)

- Corporate Board Member(s) with EHS responsibility

Union

- Workers

- Operator or senior operator in charge

- Stewards and other frontline union representatives

- Members of Union Health, Safety, and Environment Committee; Process Safety Committee, or similar committees

- Full Time Safety/Process Safety Representatives

- Local Union President or equivalent officials

- District Staff Representative

- USW Health, Safety, and Environment Director or designee

Management and Union

- Members of Union-Management Health, Safety, and Environment Committee; Process Safety Committee; or similar committee that includes representatives of both management and union(s).

Contractor employees, union representatives, supervisors, health and safety professionals, etc. should also be covered by the SWA process.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act places legal responsibility on employers to “… furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm…” But too often, employer written SWA policies say that employees and contractor employees have the authority, responsibility, and obligation [emphasis added] to use SWA if conditions warrant. This type of language must be avoided in negotiated SWA provisions to prevent employers from shifting responsibility and blaming workers.

While it is essential that workers and their union representatives have the right to use SWA without fear of consequences, management has the legal responsibility under the OSH Act to ensure workplace health and safety.

Part 3C: Situations When Stop Work Authority Could Be Useful

- Unsafe, unhealthy, or abnormal conditions

- Upset condition or event

- When unusually hazardous conditions occur during an emergency response

- Near-miss incident

- Change to scope of work, work plan, task, crew size, hours and pace of work

- Lack of experience, knowledge, understanding, or information (including when shifts are changing and when new employees are training newer employees)

- Inadequate staffing

- Fatigue

- Production and time pressures

- Emergency situation

- Environmental release

- Improper or damaged equipment use

- Lack of testing or monitoring

- Lack of permit or improper permit

- Lack of review by facility and corporate safety department

- Violation of facility or corporate policy or practice

- Violation of industry standard

- Violation of regulatory standard/rule (OSHA, EPA, state agency, etc.)

- Violation of consensus standards (American National Standards Institute, National Fire Protection Association, etc.)

It is impossible, however, to specify in detail all circumstances when a SWA process could be used effectively.

Part 3D: SWA Process

SWA is a multi-step process that should include these nine steps:

1. Stop

- When an individual perceives a situation or condition that could reasonably cause serious physical harm, chronic health effects, or damage to the facility, community, environment, that cannot be promptly resolved through routine mechanisms, he or she should promptly initiate a stop work intervention with the person(s) and operations potentially at risk and contact their union steward/union.

- If the situation or condition involves a facility operation – as opposed to a specific job or task – the individual should recommend to their supervisor or higher management if their supervisor is unavailable, that the operation or process be stopped and contact their union steward/union.

- The supervisor or other member(s) of management must alert and remove unnecessary personnel from the area, and prevent entry by others.

- The supervisor or other member(s) of management must take prompt, formal SWA actions.

- Clearly identify and describe the actions as part of the SWA process.

2. Notify and Engage

- Notify affected personnel of the SWA actions.

- Engage the relevant supervisor, union steward(s), health, safety, and environment committee, and other identified individuals promptly.

3. Investigate

- Management and union representatives (such as safety committee members) will promptly investigate the situation that led to the SWA actions and attempt to come to an agreement about its resolution.

- Subject matter experts should be involved, where necessary, at the discretion of either management or the union or both.

- Develop a hazard analysis to identify any improvements, including for hazard controls, procedures, work organization, etc.

- Include the opinions of all parties and individuals in the hazard analysis and in the documentation of the hierarchy of controls.

- Safety issues must be resolved to the satisfaction of the employee, the union representative and the employer before restarting the particular task, operation, or process or management’s assignment of other workers who are willing to complete the task, operation, or process, including subsequent shift(s).

- If it is safe to proceed without modifications, the task, operation, or process can be resumed.

- Use investigative tools, such as a camera, to document hazards.

4. Correct and Verify

- Modifications will be made to the affected area(s) according to the corrections outlined in the Stop Work issuance form or another document that specifies appropriate controls and safeguards using the hierarchy of controls.

- The affected areas will be inspected by qualified experts, with union and management participation, to verify effectiveness of interim and long-term controls.

5. Consensus to Resume

- A consensus is achieved on key issues.

- All affected individuals on all shifts will be notified of what corrective actions were implemented, how it impacts their job, and what work will recommence.

- The affected area(s) will be reopened or restarted by qualified individuals with management oversight who have restart authority.

6. Track and Assess

- To ensure collection of information about all incidents, issue a Stop Work Authority Assessment and Hazard Analysis form and complete it in all cases, including when a stop work action is quickly resolved.

- Maintain completed SWA Assessment and Hazard Analyses forms in a location readily accessible to all personnel and union representatives.

- Enter key information in a carefully designed database, including whether the SWA action triggered hazard controls and work organization or staffing changes.

- Track use of SWA and analyze trends.

7. Provide Information and Training

- Train all employees and contractor employees about SWA at least annually and when they are first employed at the facility.

- Distribute and make SWA assessment forms readily accessible to all personnel.

- Share lessons learned from specific incidents and trends with all personnel through tool box talks, bulletins, videos, etc., and incorporate in training.

- Discuss SWA process during safety and departmental meetings, with opportunities for questions and dialogue.

8. Resolve Conflicts

- Resolve conflicts through a clearly defined process that addresses the basis of the stop work action, corrective actions, and decisions to resume work/operations.

- Specify the persons in management with authority to make decisions.

- Specify the role of subject matter experts in making such determinations.

- Specify the role of corporate level and international union participation.

- Include provisions for immediate arbitration when the union and the employer disagree on SWA as to how a safe/unsafe issue is to be resolved.

9. Recognize SWA Use

- Provide positive recognition for individuals (with their permission) or groups engaged in health, safety, and environmental protection activities – and for those who exercised SWA.

For a SWA program to succeed, management must commit to and emphasize that there will be no retaliation for reporting hazards or exercising SWA – even if it is later found that a SWA action was unnecessary.

Appendix 1: USW Template for SWA

Appendix 2: SWA in 2017 California Oil Refinery Process Safety Rule (page 20)

Appendix 3: Lessons from U.S. Chemical Safety Board Investigations (pages 21 and 22)

Appendix 4: Letter from CSB Urging OSHA to Require SWA (page 23)

Appendix 5: Mine Safety and Health Act of 1997 (Mine Act) (page 23)

About the United Steelworkers Health, Safety and Environment Department

The USW’s HSE Department has five primary functions to build the union, protect health and safety and save lives:

- assisting local unions with evaluating and resolving health, safety, and environmental problems;

- assisting or conducting education and training programs for local union health and safety representatives and committees, officers, and staff representatives;

- participating in legal cases, including helping local unions to elect party status when employers contest OSHA and MSHA citations;

- advocating for better regulations, standards, and laws to protect our members and all workers; and

- helping negotiate stronger health and safety language in USW contracts with employers.

Contact

USW Health, Safety & Environment Department

60 Boulevard of the Allies – Pittsburgh, PA 15222

(412) 562-2581

safety@usw.org

Important Notes

This publication focuses on bargaining for effective Stop Work Authority (SWA) processes. The content is appropriate for many industries and sectors of the USW. However, special considerations apply to mining, heath care and a few other sectors that may not be covered in this document. For specific questions about Stop Work Authority in these sectors, contact the USW HSE Department.

This publication complements the USW’s Looking for Trouble – A Comprehensive Union-Management Safety and Health System. We call that process “looking for trouble” – identifying and preventing trouble that can get workers injured, sickened, or killed. Trouble comes in many forms, from machinery that can crush an arm, to dusts that can ignite, to awkward repetitive tasks that can cripple over time, to chemicals that can cause poisoning today or death from cancer 20 years later. Looking for such trouble, and eliminating it, is the goal of this system.

For information on the right to refuse unsafe work and addressing management retaliation for health and safety activity, see Stand Up Without Fear: Understanding the OSH Act’s Retaliation Provisions by the OSH Law Project (2020).

This publication is dedicated to the late Gerard Borne of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 13-750. Brother Borne led efforts with USW Local 13-750 and site management to develop the stop work authority process at Shell’s oil refinery and chemical plant in Norco, Louisiana. Those efforts inspired this publication.

Bargaining for Stop Work Authority to Prevent Injuries and Save Lives was written by USW Health, Safety and Environment Director Steve Sallman, and Rick Engler, a former member of the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB).

The viewpoints herein are the opinion of the United Steelworkers and reflect no official support or endorsement by the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board.

Want to Learn More?

See how the USW is making a real difference in our communities and our workplaces.