Supreme Court snatches victory away from the forces of gerrymandering

On Wednesday morning, the Supreme Court corrected a serious error by a lower federal court that, if allowed to spread throughout the judiciary, could have significantly bolstered future attempts to draw gerrymandered districts.

Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections concerns 12 Virginia state legislative districts that were allegedly drawn as racial gerrymanders. Each district was drawn to ensure that black voters would make up at least 55 percent of the district’s voters. The state claims it did this in order to comply with the Voting Rights Act as it stood prior to the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision gutting much of the law.

The Court largely avoided the question of whether 11 of the 12 districts were drawn lawfully, sending the districts back down to the lower court for reconsideration. It did, however, correct a mistake by the lower court that would have effectively allowed illegal gerrymanders to thrive so long as they are pretty.

“An essential premise of” the lower court’s opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy explained on behalf of the Court, is that map is not an illegal racial gerrymander unless “there is an ‘actual conflict between traditional redistricting criteria and race that leads to the subordination of the former.’”

These traditional criteria include traits such as compactness and continuity, which the courts have historically used as proxies to sort good maps from bad. If a district is ugly and misshapen — if it stretches, like a salamander, throughout many distant parts of the state — then courts are more likely to deem it an unlawful gerrymander. If a state’s maps are neat and tidy, however, they are more likely to survive.

But, as Kennedy explains, compliance with these traditional criteria is not, in and of itself, sufficient reason to declare a map lawful. Quoting an earlier Supreme Court opinion, Kennedy explains that “shape is relevant not because bizarreness is a necessary element of the constitutional wrong or a threshold requirement of proof, but because it may be persuasive circumstantial evidence that race for its own sake, and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale.”

Since the lower court’s error has now been corrected, an otherwise illegal map will not survive judicial scrutiny simply because it looks nice. That’s good news for opponents of gerrymandering — especially if the Supreme Court ever comes around to the view that partisan gerrymandering (as opposed to racial gerrymandering) is unconstitutional.

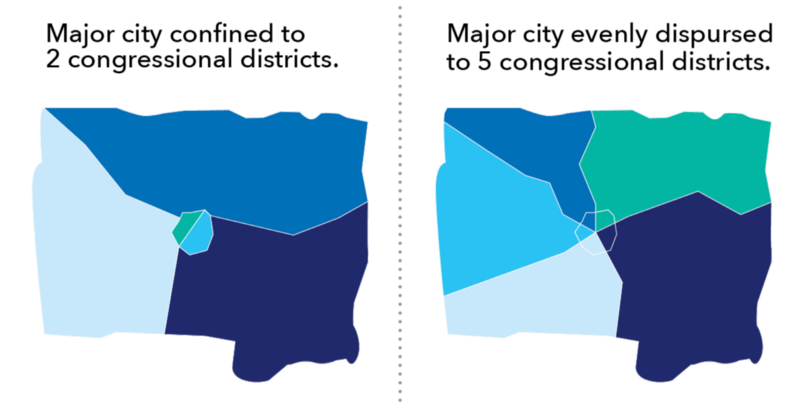

One of the biggest challenges facing Democrats right now is geography. Because liberal voters tend to cluster in compact urban districts, while more conservative voters tend to spread out over more land, states that use traditional redistricting criteria such as compactness typically produce maps that favor Republicans. Consider, for example, this map:

CREDIT: ThinkProgress/Adam Peck

In a state where Democrats are clustered in the city and Republicans spread out in rural and suburban areas, the map on the left will produce two Democratic districts and three Republican districts, thereby favoring the GOP. The map on the right, by contrast, is more likely to produce five competitive districts where either party has a shot at prevailing.

A legal rule that enshrines compliance with traditional criteria as a defense to a gerrymandering lawsuit threatens to entrench the GOP’s dominance in the redistricting wars, even if the justices eventually started striking down partisan gerrymanders. This is not an academic question, moreover, as the Supreme Court is likely to review a lower court decision striking down Wisconsin’s state assembly maps as an unconstitutional gerrymander in its next term.